In 2009, I was living in Houston when the Houston Museum of Natural Science exhibited fifteen of the thousands of terra cotta ceramic soldiers dug up in China over the last 35 years. I missed that show, but I have since learned more about the figures and their importance in archeology and the art world.

In 2009, I was living in Houston when the Houston Museum of Natural Science exhibited fifteen of the thousands of terra cotta ceramic soldiers dug up in China over the last 35 years. I missed that show, but I have since learned more about the figures and their importance in archeology and the art world.

The life-size figures were created around 2,200 years ago for the tomb of the first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi, who conquered the many warring provinces to unite China 221 B.C. His name, Qin, is pronounced “chin” and is the origin of the country’s name.

To conquer an area that large and create an empire, the man in charge had to be pretty ruthless. He defeated and enslaved opposing provinces and was known as a vicious dictator. Qin had an army of thousands of flesh-and-blood soldiers on earth, but wanted to make sure he could go on kicking ass in the afterlife too. To ensure his eternal dominance, Emperor Qin had about 8,000 life-size terra cotta clay warriors made to be buried in and around his tomb.

The burial site was discovered in 1974 and has a wealth of information to teach us about ancient China. This is especially important because the earliest written records of the time occur around a century after the emperor’s rule. So what can we learn from thousands of ceramic figures buried 200 years before Christ?

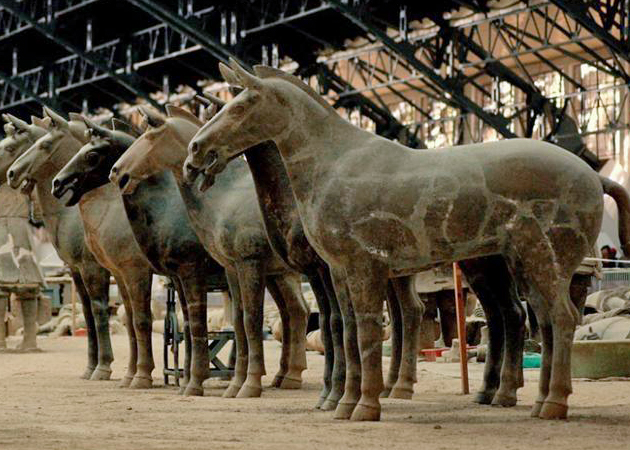

First, we can understand how the ancient Chinese viewed the afterlife: as a continuation of life on earth. They buried precious objects with the dead so they could continue to party in style. Before Emperor Qin’s rule, we see that there were very few statues or dolls buried with the dead. That’s because the wealthy were entombed with their servants and animals killed in ritual sacrifice. By Qin’s time, though, the custom had changed to the less-creepy practice of surrounding the dearly departed with statues of his servants rather than the real thing. Emperor Qin also included life-size acrobats, horses, chariots, weight lifters, and exotic animals, all made of ceramic or bronze.

We can also learn from these artworks about the production methods available at the time. These 8,000 soldiers were all cast from molds that could be mixed and matched so each figure was unique. Clay shaped in leg molds would be joined with molded clay torsos, arms, and heads. Then fine craftsmen would sculpt the detailed facial features, armor, and hairstyles that made each one an individual.

The figures also tell us about technology available in China at the time. The crossbows and all 40,000 arrowheads were battle-grade weapons. They were made from the strongest bronze available and sharpened on a grinding wheel for use in battle. By studying the weapons, we can see the technology available at the time and how seriously the craftsmen took their jobs of protecting the emperor in the afterlife.

The artists who created these figures did their job (communicating what a bad ass Emperor Qin was!). They also gave us a wealth of information about ancient China without even meaning to.